Choosing macOS Computer Names Wisely

How do you tell one machine from another?

In the physical world, referring to a specific object may be a simple task where one can resort to the object’s location, to its visual markers like form, color, and labels or to a telling name. In the digital world of bits and bytes, on the other hand, nothing exceeds a unique identifier, especially when it bears the signs of universal (or at least global) uniqueness, which denotes, in essence, a random identifier. While the latter may be an ideal solution from a purely logical perspective, it is not very intuitive in human-machine interaction. That is because humans are not very good at handling random strings of text but rather prefer names that have meaning to them. So, when humans need to identify an object in the digital world, the solution usually turns out to be a name that is “human-readable” and at the same time unique enough to allow for a sufficient amount of non-duplicate names.

When it comes to machine names, unfortunately, macOS does not handle this solution very well. At least not by default.

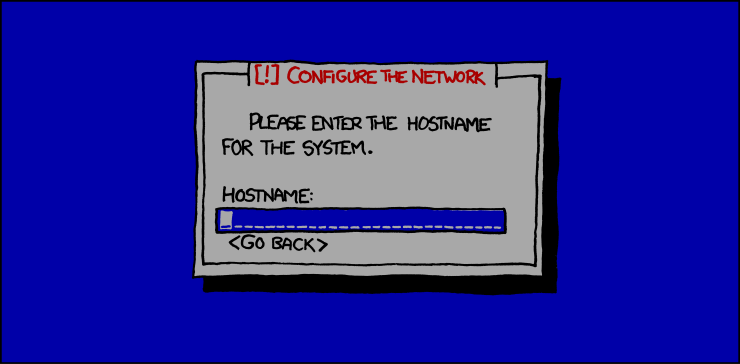

Permanence (excerpt) by xkcd under CC BY-NC 2.5

Apple devices are automatically named after their owner: “Bob’s iPhone”, “Susan’s iMac” and so on. While this seems charmingly simple and may work well in small environments like a family home or a small business, in the context of an enterprise with hundreds or even thousands of workstations the default solution will not “just work”, obviously. As soon as two Susans each have an iMac, both machines will have the same name. Which is bad. Because of that, enterprise IT departments usually follow a naming convention that makes every machine uniquely identifiable. While there is hardly one naming convention that fits all, most of them make use of some of the following factors:

- User name

- Department

- Site

- Functional role

- Sequential numbering

- Serial number

- MAC address

- Operating system

Because a user name and especially a department may not be unique enough on their own, it is quite common to combine both factors with each other or with additional factors. Serial numbers and MAC addresses, on the other hand, might be regarded as too verbose, hard to communicate or even as sensitive information.

But whatever naming convention an IT department follows, the inevitable question is: what is the right place to store the machine name on a macOS system?

Computer Name

Indeed, macOS offers several places that may store a machine identifier. Users naturally resort to the computer name that can be easily set via the System Preferences GUI and features prominently in everyday contexts like Network Discovery, AirDrop or iCloud. There is a caveat, though, that every system admin spots from a mile away: the computer name allows spaces and special characters – remember: “Susan’s iMac“. This is rarely acceptable in system administration and allowing it makes the machine name error-prone and therefore not a feasible choice when maintaining enterprise machines.

Luckily, macOS also offers two other options, namely the local hostname and the (regular) hostname. But what is their intended purpose? And which one is suited best?

Local Hostname

Apple explains the local hostname like this:

Your computer’s local hostname, or local network name, is displayed on your local network so others on the network can connect to your Mac. It also identifies your Mac to Bonjour-compatible services.It also explains how the local hostname is usually constructed:

The local network name is your computer’s name with .local added, and any spaces are replaced with hyphens (-).And elsewhere:

If your Mac has the exact name of another Mac on your local network, a number is added to the local network name.Add to these statements that any special characters in the computer name will get replaced by their regular character counterparts or completely stripped and that the length of the local hostname is limited to 64 characters, and you get a serious contestant for the best place to store a machine name.

Hostname

The hostname is the probably oldest facility to name a macOS system with the respective API being part of its FreeBSD heritage. The hostname’s purpose is to simply hold a name for the system and it can easily be looked up by running the hostname command from the terminal. How the hostname is usually determined on macOS, is an entirely different story, though. Searching the Internet for clues turns up exactly one official document which dates back to 2005: The Mac OS X Server 10.4 Worksheet.

This setting causes the server’s host name to be the first name that’s true in this list:

- The name provided by the DHCP or BootP server for the primary IP address

- The first name returned by a reverse DNS (address-to-name) query for the primary IP address

- The local hostname

- The name “localhost”We never observed “localhost” in our own tests but since the local hostname itself is a derivative as outlined above, the last line should probably read “The computer name“ by now. In case you were wondering what happens if the computer name was not set, that is a really good question which we have no answer for because we never managed to not set it. The System Preferences GUI does not allow an empty text field and the scutil CLI automatically replaces an empty string with the machine’s model name, e.g. “MacBook Pro“.

What’s probably most interesting to a system administrator is the fact that the hostname, unlike the local hostname, is allowed to contain spaces and special characters. That makes the hostname as bad a choice as the computer name to store the machine name. Top that off with more or less unpredictable name changes whenever the machine’s network connection changes, at least when relying on the automatic naming mechanisms, and hostname is definitely out of the game.

Three Names, One Machine

The scutil man page offers the probably most comprehensive description for the three names:

ComputerName The user-friendly name for the system.

LocalHostName The local (Bonjour) host name.

HostName The name associated with hostname(1) and gethostname(3).A Practical Solution

To answer the question from above where the macOS machine name should ideally be stored, the most simple and pragmatic solution is: everywhere. When computer name, local hostname and hostname all match exactly, there will never be a chance for confusion when any of the three names pop up on the network, in log files, in web dashboards or anywhere else.

But wouldn’t it be sufficient to simply set the computer name and let the system handle local hostname and hostname automatically? Even if the computer name did not contain any spaces or special characters, which would at least make the local hostname a match, the system tries to be helpful and automatically adds a DNS domain suffix to the hostname.

So, the practical solution is to set all three names explicitly. The most comprehensive tool that allows to explicitly set the computer name, local hostname and hostname is scutil:

% scutil —-set ComputerName "HAL9000"

% scutil -—set LocalHostName "HAL9000"

% scutil -—set HostName "HAL9000"

What The Network Sees

So you went out of your way and explicitly set the computer name, local hostname, and hostname but you still see your machine lingering on the network under another name? What routers, IP scanners, and non-macOS systems regularly use for identification is the NetBIOS name that can be retrieved over the network similar to Bonjour names. On macOS, the NetBIOS name is derived from the local hostname but of course, it can also be set explicitly in the System Preferences:

System Preferences > Network > Advanced… > WINS > NetBIOS NameThe uberAgent Host Identifier

uberAgent on macOS uses the local hostname as the host identifier when sending data to backends. Since the local hostname does not allow spaces or special characters, it automatically enforces the basic backend requirements for host identifiers. This also allows for automatic host naming which otherwise, using the (regular) hostname, could yield unpredictable results whenever the network connection changed. It also ensures that backends always see the exact same name as an administrator would on the machine, because not uberAgent but the macOS system itself performs the automatic name sanitization if necessary.

About uberAgent

The uberAgent product family offers innovative digital employee experience monitoring and endpoint security analytics for Windows and macOS.

uberAgent UXM highlights include detailed information about boot and logon duration, application unresponsiveness detection, network reliability drill-downs, process startup duration, application usage metering, browser performance, web app metrics, and Citrix insights. All these varied aspects of system performance and reliability are smartly brought together in the Experience Score dashboard.

uberAgent ESA excels with a sophisticated Threat Detection Engine, endpoint security & compliance rating, the uAQL query language, detection of risky activity, DNS query monitoring, hash calculation, registry monitoring, and Authenticode signature verification. uberAgent ESA comes with Sysmon and Sigma rule converters, a graphical rule editor, and uses a simple yet powerful query language instead of XML.

About vast limits

vast limits GmbH is the company behind uberAgent, the innovative digital employee experience monitoring and endpoint security analytics product. vast limits’ customer list includes organizations from industries like finance, healthcare, professional services, and education, ranging from medium-sized businesses to global enterprises. vast limits’ network of qualified solution partners ensures best-in-class service and support anywhere in the world.